Decrypting Viscosity Passwords

Recovering saved Viscosity credentials

During a red team op, retrieving plain text credentials is an integral part of ensuring operational success. Plaintext credentials allow you more flexibility in the kinds of attacks you’re able to do, and depending on what credentials are stored, can give you additional access to an environment.

Keylogging is a very reliable way to recover credentials, however it can take a while, and the user may not even type their password in, they may rely on it being remembered by their browser or a password manager. Because of this, I’m always looking for new places that store credentials, and how they can be abused. One day while doing some maintenance our infrastructure, it occurred to me that Viscosity allows users to save credentials so that they don’t have to be entered every time they connect. It piqued my interest, and I decided I wanted to learn a little bit about how those credentials are stored, and whether they can be recovered or not.

Note: I think it’s important to show the process of how I figured it out, but if you’re only interested in the technical details skip to the section labeled “Diving Deeper”

How it works

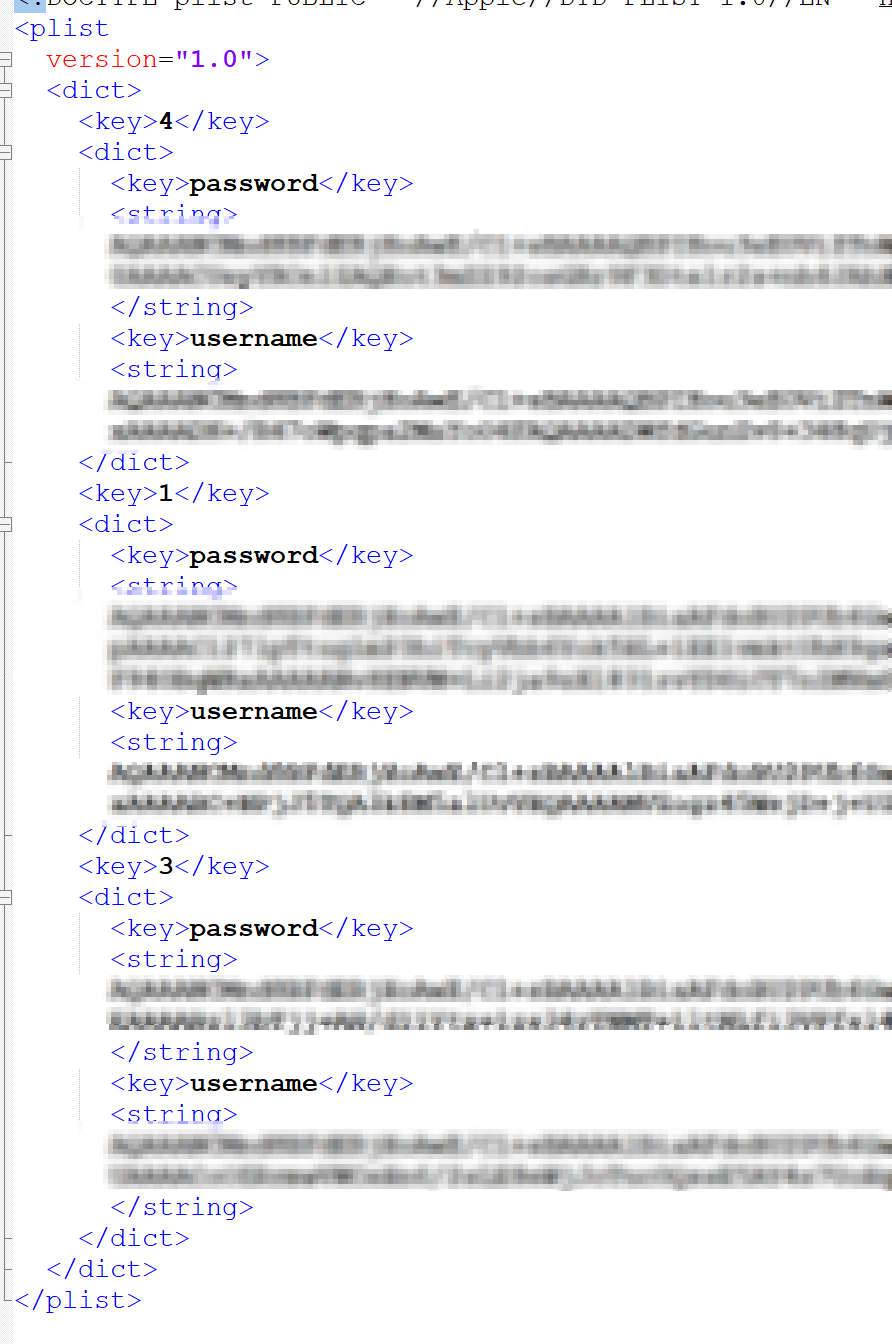

After a quick google search, I came across this forum post which identified the location for saved credentials is a file called LoginInfo.xml stored in %AppData%\Viscosity\. From here, I decided to take a look at the XML file, hoping that it would be in a format that was easily recoverable or even plaintext, the file looks like this:

It turns out it’s a plist containing keys for each connection with each connection containing subkeys that identify the saved Username and Password for the user. I saw Base64 encoding, however it looked too long to just be the Base64 encoded username/password. A quick decode of the string confirmed my suspicions that it wasn’t going to be that easy. Before I dove too deep, I decided to look up to see if anyone had already documented password recovery for these files. Unfortunately no such tool existed, and according to this forum post there is no way to recover the saved credentials. Well that’s no fun, so I decided to set out and see if it was actually possible to recover these credentials.

First I needed to figure out how they’re protecting these credentials. I went back and did some more googling and came across this. The developer indicated that by design LoginInfo.xml files cannot be moved from one machine to another, which indicated that something on the machine is handling the encryption portion. Anyone who has read my blog before, can get an idea of where this is going, DPAPI!

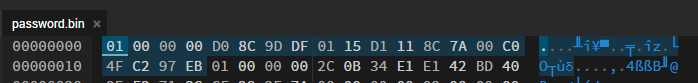

The nice thing about DPAPI blobs, is they’re pretty easy to identify. DPAPI blobs begin with a standard set of bytes that indicate what it is, these bytes are 01 00 00 00 D0 8C 9D DF 01 15 D1 11 8C 7A 00 C0 4F C2 97 EB. A lot of applications like to store these blobs in Base64 encoded format so you’ll have to decode it to a byte array first, and then check the array. If we take the code from my previous blog post about decrypting VEEAM passwords and input one of our found strings in it, we’ll get a password.bin file. From here, we can take that password.bin file and load it into a hex editor and we’ll see something neat:

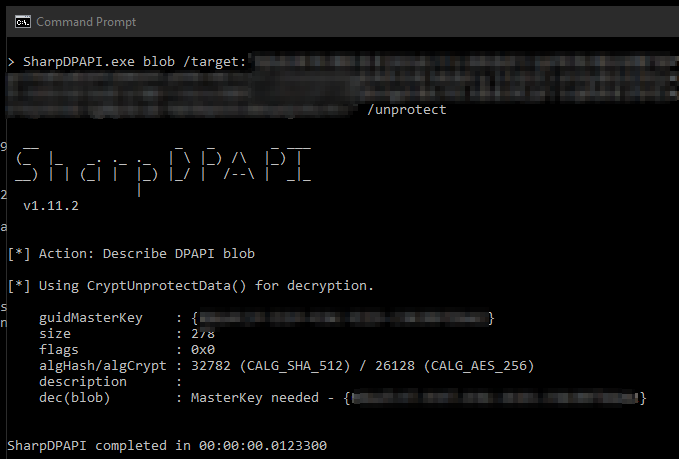

The beginning of our file matches the same byte format as the one that identifies DPAPI blobs! This will be easy I hoped, so I pulled out SharpDPAPI and attempted to decrypt it. So I ran SharpDPAPI.exe /target:"password.bin" /unprotect and got an error:

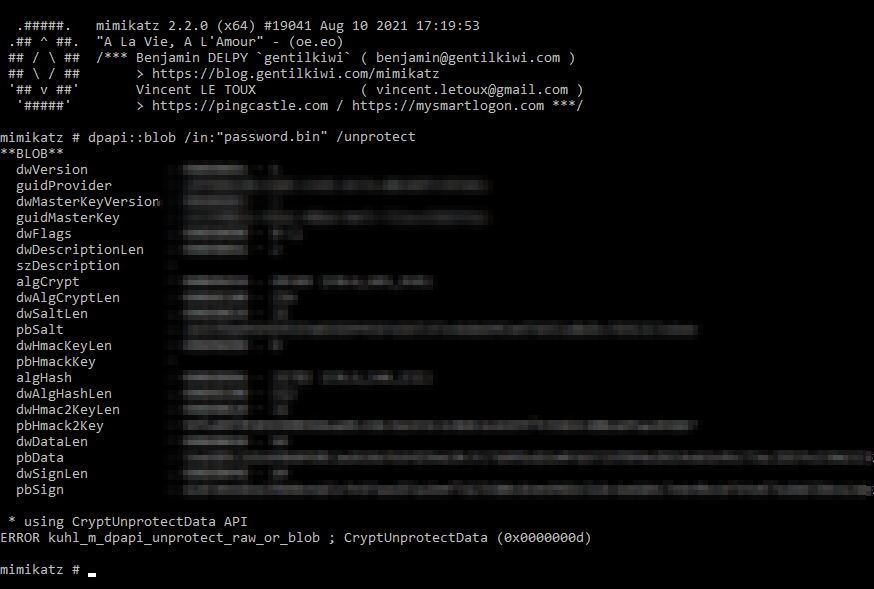

That’s weird, I’m already in my own user context? So I tried with mimikatz

Crap, okay I guess we’ll have to do it manually then. Mimikatz errored, I have no idea what the error means, but SharpDPAPI was slightly more understandable so I started with that. For some reason, it was unable to access the specified MasterKey so I decided to pull it manually using the mimikatz command sekurlsa::dpapi

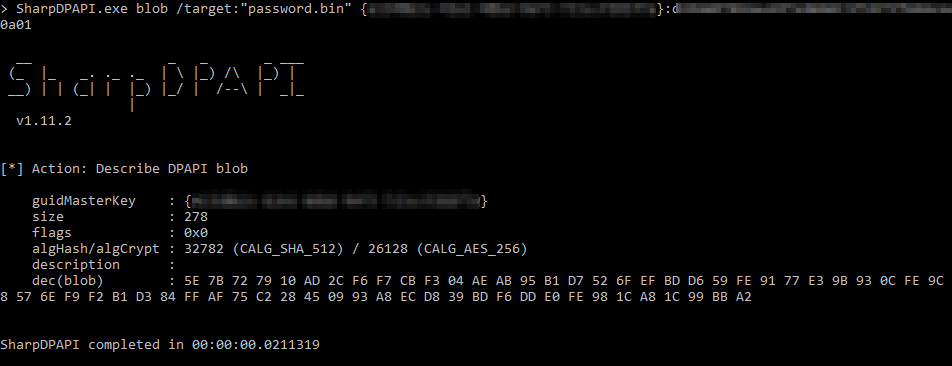

Scrolling down, I found the credential DPAPI GUID and SHA1 values I needed in order to decrypt. So I gave that a try with the following command:

SharpDPAPI.exe blob /target:"password.bin" {guid}:sha1

Success maybe?

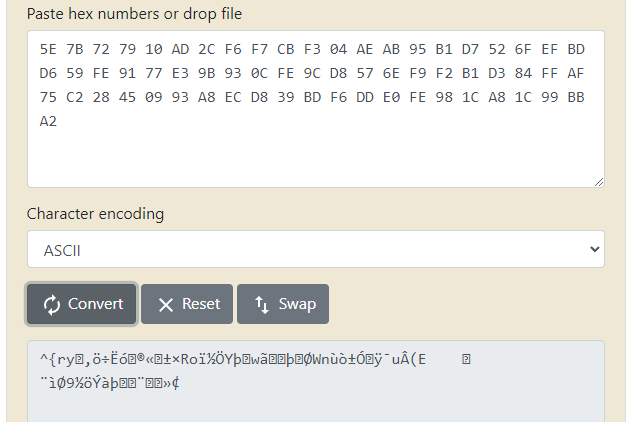

Darn. That’s definitely not a password. After a bit of back and forth with @subat0mik, he recommended I try out the DataProtectioNDecryptor application created by Nirsoft. I did, and the application confirmed that I was not decrypting the blobs successfully. @harmj0y eventually chimed in noting that CryptProtectData can be provided with additional entropy which would make decryption more difficult. This seemed like the likely culprit, so I would need to dive a bit deeper to figure out what was really happening.

Diving deeper

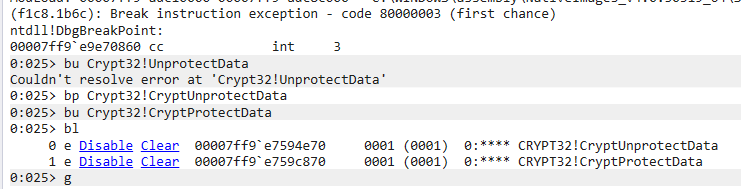

@subat0mik pointed me to an article created by Quentin Kaiser (@QKaiser) detailing his process of reversing the pulse secure client credentials store which also contained additional entropy. The article is a great read albeit the formatting has broken slightly and can be found here. First I downloaded WinDBG from the Windows Store, while not the nicest looking application, it was good enough. With a bit of help (Thanks @willmonk!) it will be able to help me accomplish what I needed to.

Since I already knew what function was being called to encrypt and decrypt the data I went ahead and set my breakpoint with bp Crypt32!CryptUnprotectData I then entered the g command in order to allow the process to continue execution:

After setting your breakpoints, you can confirm that your breakpoint was set properly using the bl command. I also added a breakpoint for CryptProtectData however, I ended up not needing that in this case.

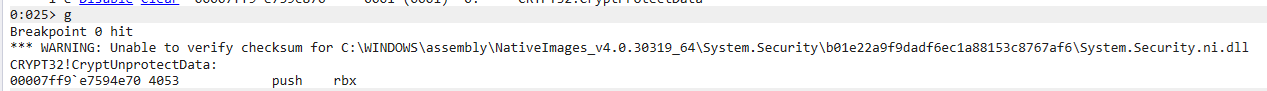

Next, I connected to the VPN that had my credentials saved in Viscosity. It was here that my breakpoint was hit, and execution was immediately stopped:

There are a few quick things you need to understand about function calls in Windows before I continue. When a function is called and parameters are passed to a function, where these parameters are stored is dependant on where in the order the parameters are. This information can be found here on MSDN. However the quick version is, the first four parameters are stored in CPU registers, and anything beyond that gets pushed to the stack. So if we have a function like

AddNumbers(int num1, int num2, int num3, int num4, int num5, int num6)

Their locations in memory would be:

| Name | Location |

| num1 | RCX |

| num2 | RDX |

| num3 | R8 |

| num4 | R9 |

| num5 | Stack |

| num6 | Stack |

We’re interested in the CryptUnprotectData function which looks like the following:

CryptUnprotectData(DATA_BLOB *pDataIn, LPWSTR *ppszDataDescr, DATA_BLOB *pOptionalEntropy, PVOID pvReserved, CRYPTPROTECT_PROMPTSTRUCT *pPromptStruct, DWORD dwFlags, DATA_BLOB *pDataOut)

So putting in in order with our above chart, their locations would look like this:

| Name | Location |

| *pDataIn | RCX |

| *ppszDataDescr | RDX |

| *pOptionalEntropy | R8 |

| pvReserved | R9 |

| *pPromptStruct | Stack |

| dwFlags | Stack |

| *pDataOut | Stack |

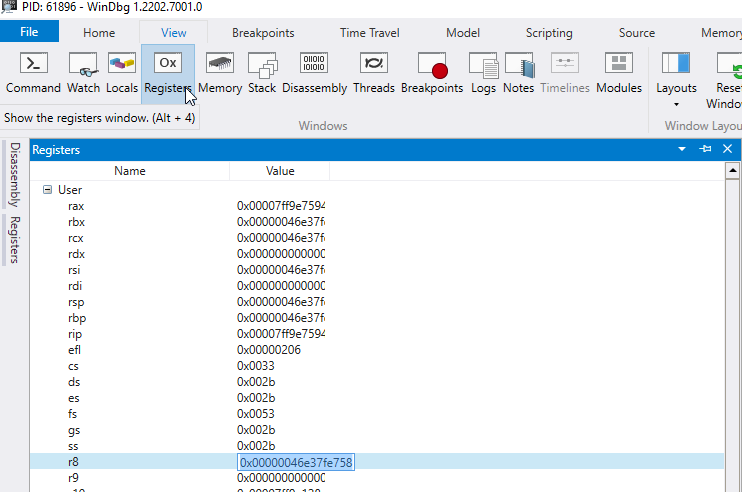

The thing we don’t already know out of those parameters is *pOptionalEntropy which is a pointer to the Entropy data that we’re looking for. Since it’s the 3rd parameter being passed, that means it’s value will be stored in the register R8. So now we can go back and look at the registers in WinDBG:

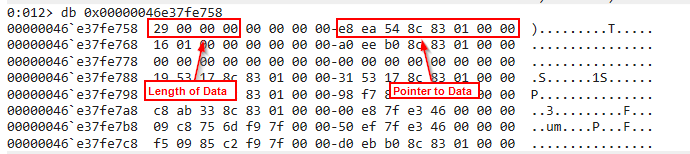

So in our case, we can see that the register R8 has the value 0x00000046e37fe758. Since the CryptUnprotectData function is looking for a pointer to a DATA_BLOB struct, we take a look at what we can find at that memory location with the command db 0x00000046e37fe758 or even easier db @r8. To understand what we’re looking at we’re going to have to get a quick idea of what the DATA_BLOB struct looks like. The documentation can be found here but it’s essentially a small struct with two properties. The first is how big the data is, and the second is a pointer to the data. So in the screenshot below, I’ve separated the two properties so you can see it easier:

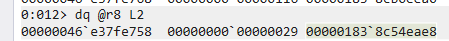

Since the DATA_BLOB struct requests a pointer to the data and not the data itself, we need to dump the memory where this pointer is referencing. We need to remember that this pointer is going to be in little endian format, which means we need to reverse it. So the memory location ends up being 0x000001838c54eae8, you can have WinDBG automagically reverse it for you by using dq instead of db like this:

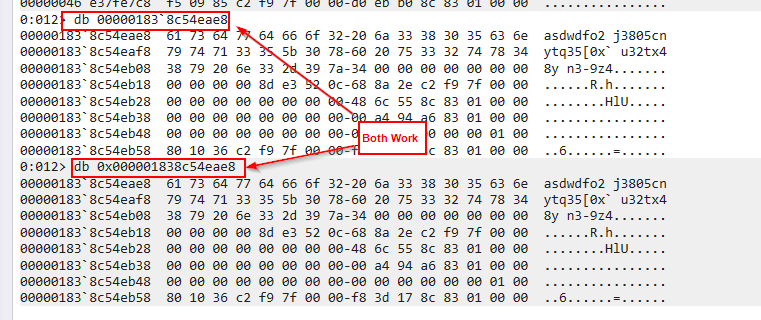

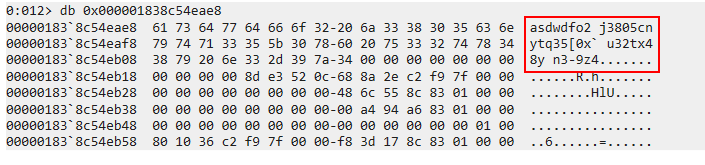

So you can directly copy 00000183`8c54eae8 or reverse it into 0x000001838c54eae8 and use it within the db command to view the section of memory that pointer is pointing to:

Now we have access to a memory location containing some data that looks right! Looking back at the length property of the DATA_BLOB we were looking at indicates it has a length of 29 but we need to remember that this is a hex value, so in decimal it actually is 41, luckily for us, that’s exactly how long this string is!

It looks like we’ve successfully found our entropy string, we can attempt to decrypt the DPAPI blob!

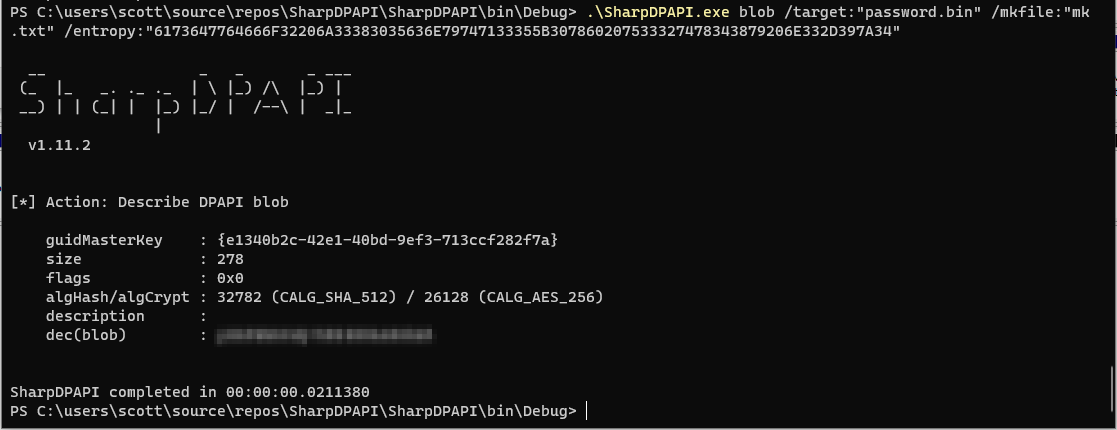

First we’ll need to convert our entropy string to a hexstring to be accepted by SharpDPAPI. So our string will be 6173647764666F32206A33383035636E79747133355B307860207533327478343879206E332D397A34

then we can enter it into our previou SharpDPAPI command using the /entropy flag like so:

Victory!

I confirmed that the value returned was the same value as the password I had stored in my password manager, which also means we had successfully identified the entropy string. I tried this same entropy string with the other saved credentials in this file and it worked for all of them, which means that the salt is the same for each entry. However, how does the application get this value?

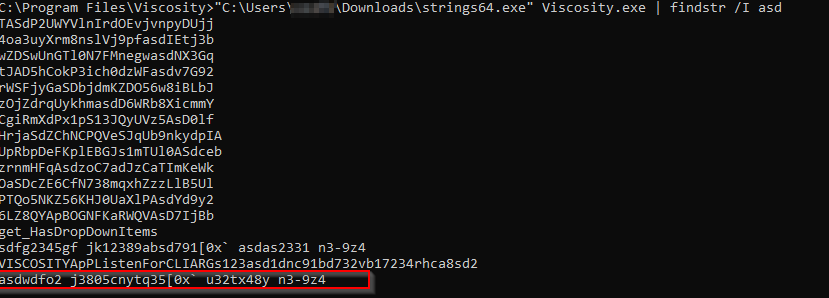

I decided to see if I could find the string stored in a file on my operating system. However, I ended up getting lucky and found it pretty quickly. After running strings.exe on the Viscosity.exe executable, I did a search for the entropy string and there it was!

After confirming with a few coworkers, it seems like this entropy string is hardcoded inside the executable itself! So at least between the same versions of Viscosity you’ll be able to use the string asdwdfo2 j3805cnytq35[0x` u32tx48y n3-9z4 as your salt. This may or may not change between versions, but at least we now have a way of recovering the value without too much fuss.